What scientific ideas are worth pursuing?

A unified model of scientific elegance and convergence.

One of the things about studying something like physics is that you learn basically nothing about how to do science.

There are no classes on how progress in science happens or how to pick worthwhile research questions.

I guess you’re supposed to pick this up by osmosis or something.

Does this work? No. At best you’ll hear some hushed comment about Kuhn’s paradigm shifts or “The Scientific Method”.

This is a big factor in why there is so little progress.

Virtually all energy and resources are wasted on pointless projects.

This could be avoided if only people spent some time actually thinking about scientific progress in a systematic way and about what questions are actually worth pursuing.

So here’s my attempt to do just that.

What do we actually want?

In a nutshell, we want to find increasingly powerful explanations for how nature works that are backed up by data and logic.

On the one hand, explanations get more powerful when they help us understand something we previously couldn’t. When a new model helps us make sense of a previous unexplained phenomenon, that’s progress.

But on the other hand, explanations get more powerful when they are able to explain the same in simpler ways. A model that provides a unified explanation of dozens of phenomena that previously required different models is more powerful even if it doesn’t explain anything previously unexplained.

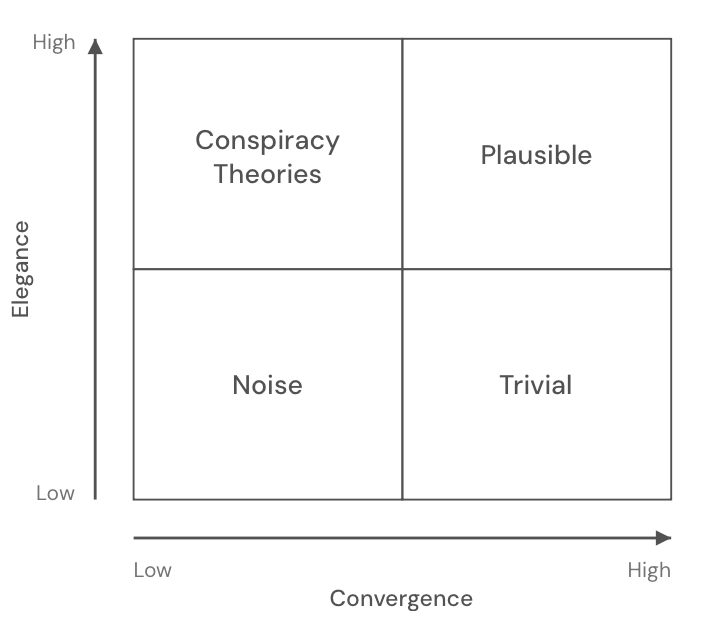

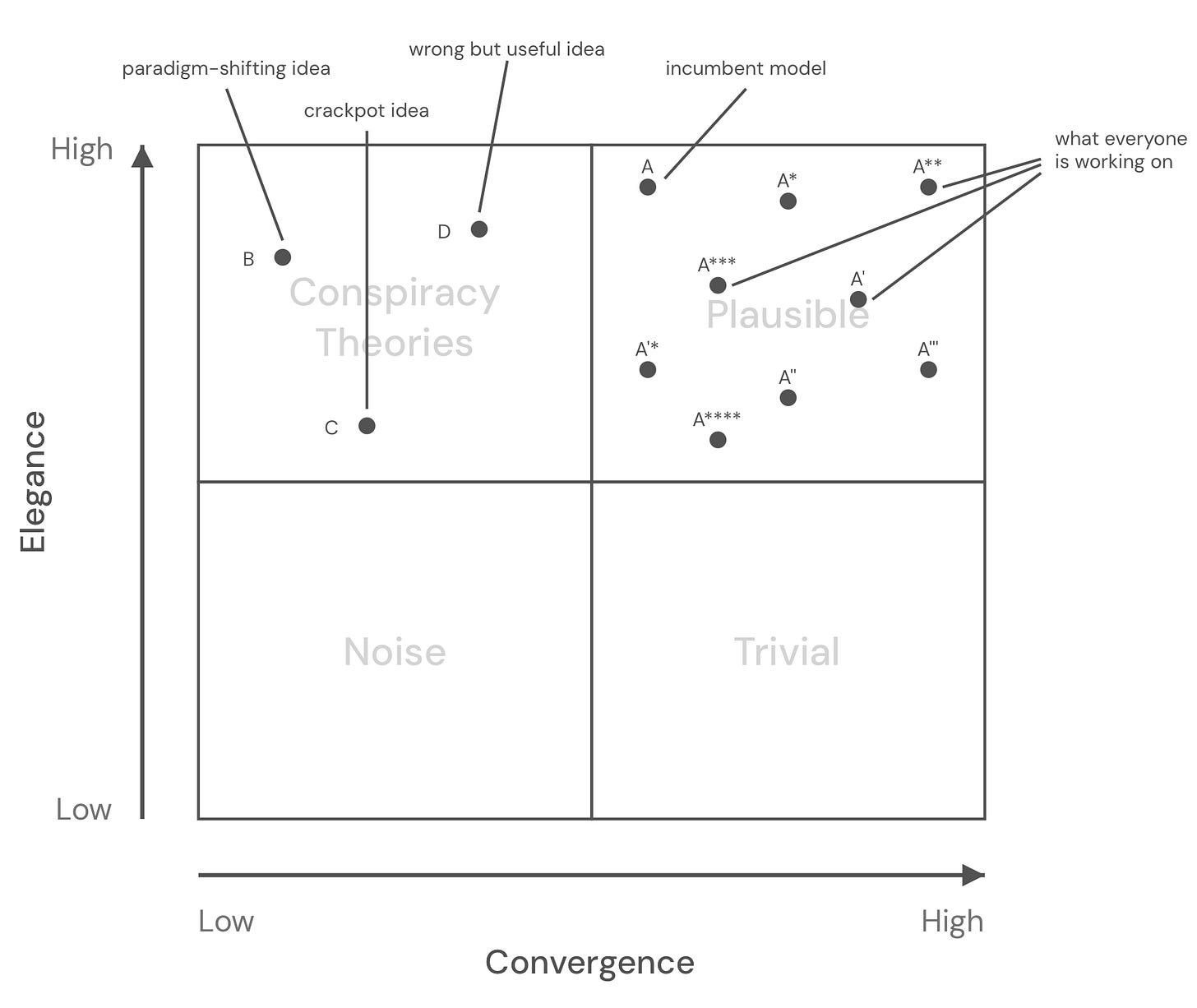

A useful way to think about this is in terms of elegance and convergence:1

Elegance here means “power” or “multi-aptness”. The more domains/levels/phenomena a given explanation illuminates without flattening them, the more elegant it is. Think: few degrees of freedom for many consequences.2

Convergence means that multiple independent lines of evidence point towards it. So convergence gives us bias reduction and trustworthiness. Think: data and constraints (e.g. mathematical consistency) squeeze it into place. Crucially, convergence is not a static property but it’s a trajectory. Philosopher Imre Lakatos captured this with his distinction between “progressive” and “degenerating” research programs. What matters is the derivative: are new developments tightening or loosening the constraints?

Grand Unified Theories provide a clean example. In the early 1980s, extrapolating the three coupling constants of the Standard Model to high energies showed them nearly meeting at a single point. That’s exactly what you’d expect if there’s one unified force. But as measurements became more precise throughout the 80s and 90s, it became clear that the three lines actually miss each other by quite a bit. The convergence that once made GUTs compelling evaporated.

With this in mind, we can draft a 2x2 chart that will be helpful in understanding models of scientific progress and problem selection.

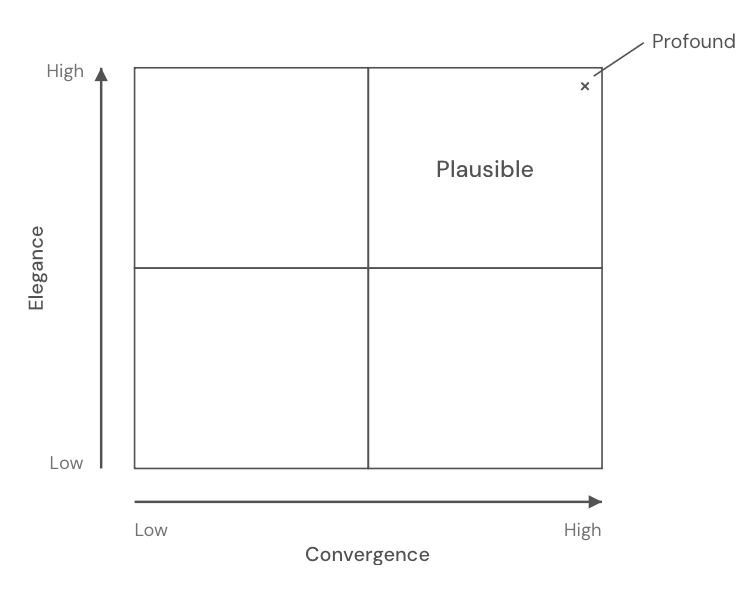

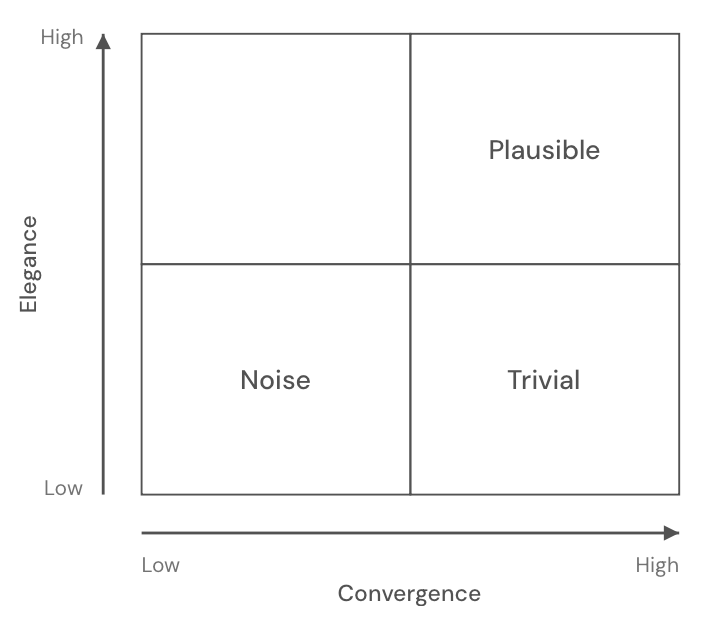

We call an explanation with the right balance between elegance and convergence plausible.

Plausible doesn’t mean it’s true. It only means it’s worth taking seriously.

At the highest level of elegance and convergence we find ideas that are profound.

For example, Maxwell’s theory of electromagnetism is profound because it provides an elegant explanation of a vast number of phenomena and has a ton of experimental data plus mathematical consistency to back it up.

It’s the gold standard of what we’re trying to achieve in science.

Most explanations do not meet this standard or come even close.

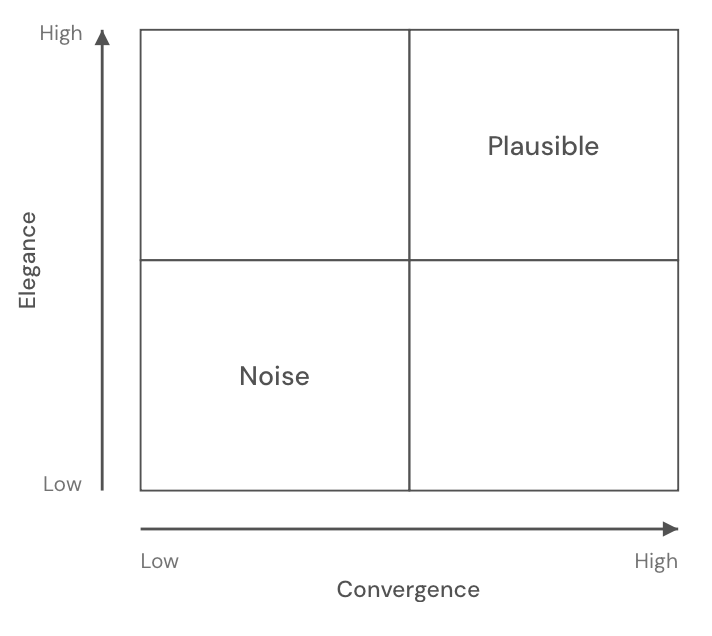

Low convergence and low elegance explanations are usually not worth talking about and we can just discard them as noise.

An inelegant explanation that is backed by a ton of data and mathematical consistency is trivial. With enough structural complexity you can easily explain anything.

The thing about trivial explanations is not that they’re false. But they’re not powerful. Trivial explanations provide little to no insight.

The infamous epicycles, for example, are placed in this quadrant. They are not completely trivial but close.

And lastly, highly elegant explanations with no convergence toward them are what we call conspiracy theories.

This framework might seem trivial (hah) but it will become clear in a minute why it’s worth considering.

To start, note that we need a plausibility framework because our resources and time are finite and hence we can’t do a random search.

We don’t want to test any hypothesis anyone can come up with.

“Cutting my hair will increase the GDP in Burundi.”

“Alphabetizing my spice rack will slow the Lambert Glacier’s melt rate by 0.0001 percent.”

It is obvious in these instances that testing these hypotheses is a waste of time and resources.

Things are less obvious as soon as you start dressing your hypothesis in fashionable, consistent math.

For example, there are infinitely many well-defined quantum field theory models that look just like the Standard Model at low energies. In other words, no current low-energy experiment can disprove them.

Hence without a plausibility filter, you are not doing directed search. You are wasting billions performing a random search inside an infinitely large hypothesis space. But that doesn’t stop researchers from publishing hundreds of papers on such models every year.

Abusing the Machinery

Where things get even more tricky is that people often abuse this machinery to bullshit others and themselves.

They do this by freely oscillating between different ways of presenting their explanations to make them seem more plausible than they really are. This is the famous Motte-and-Bailey strategy.

You first present a strong statement and when people start pointing out problems with it you retreat to a different one that is easier to defend.

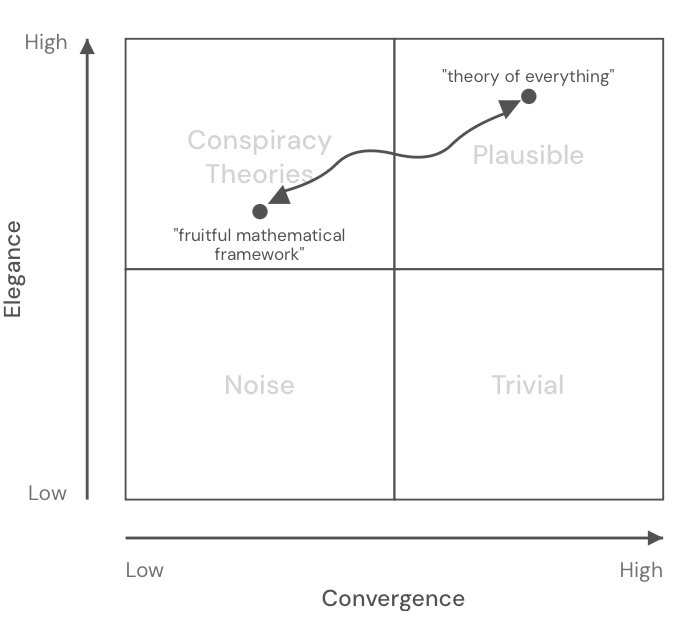

For example, what if simply by replacing point particles with strings our theory would become so constrained that we could explain why we observe the elementary particle zoo. That’s an extremely elegant idea that became popular in the 80s. Back then there was reasonable hope that mathematical and experimental convergence would materialize. So String Theory seemed like a plausible explanation worth taking seriously. Now, 40 years later we know that there is no formal convergence. String Theory has a landscape problem with more than 10⁵⁰⁰ ways of constructing string theory models. Also, still zero experimental evidence convincingly pointing towards String Theory. It slowly morphed from a theory of everything into a theory of anything.

But the reason so many people keep working on String Theory is that it can be laundered across quadrants. The original plausible story is used to excite students and the public. When pressed by people who know where the bodies are buried, researchers quickly retreat to safer but less plausible claims in a different corner of the map:

We could also call this faux elegance:

Bailey (marketed claim): “One simple idea explains everything.”

Motte (defensive retreat): “Sure it needs a lot of extra clauses, exceptions, knobs, hidden machinery… but the core idea is still ‘simple’ and the math is ‘beautiful’.”

To use again Imre Lakatos terminology: in the 1980s, string theory was progressive: each new result seemed to tighten the constraints. Today it’s degenerating: each new development (the landscape, the multiverse, etc.) loosens them. The trajectory reversed, but the rhetoric didn’t.

There are also much simpler examples of how people abuse our plausibility machinery.

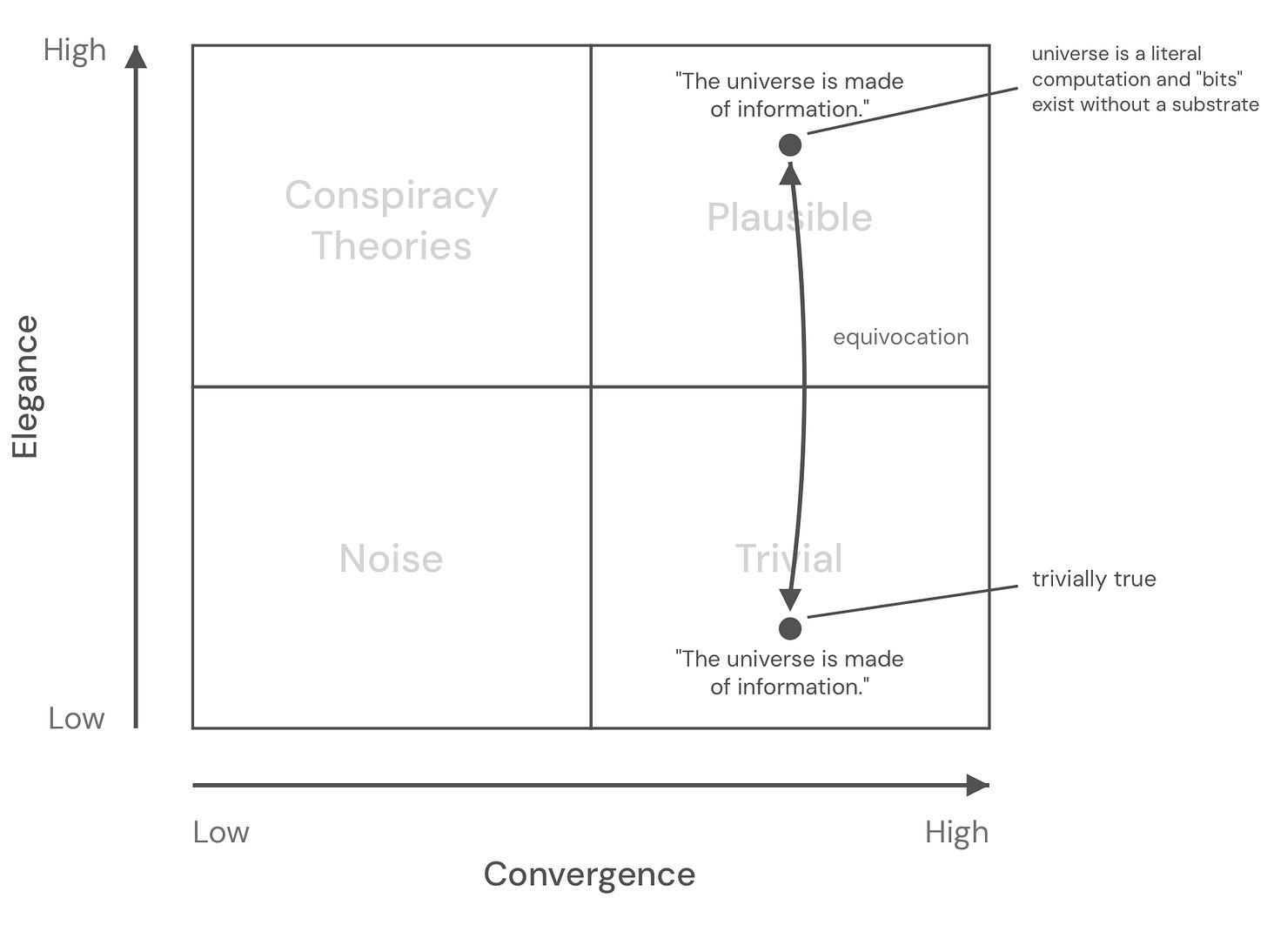

Take the classic example: “The universe is made of information.”

People say this and everybody nods thinking “Oh, that’s very profound…”.

But notice what’s really going on here.

Information is a deep, nuanced concept. So when someone drops an undeniably true statement about it, we feel like we learn something profound.

But in reality, we’ve been given a triviality.

In its trivial reading, the statement is a tautology: any physical state can be described as data. To do physics at all is to map nature onto information. It’s like saying, “A book is made of alphabet.” It’s true, but it tells you nothing about the story.

The “deeper truth” the statement hints at is that the universe is a literal computation or that “bits” exist without a substrate is unsupported by facts.3

Daniel Dennett calls this a deepity. Deepities are statements that are pretending to give you multi-aptness, when in fact what you’re getting is triviality.4

The trick is that a deepity always has two meanings: one that is true but trivial, and another that sounds profound, but is largely unsupported. It’s bullshitting through equivocation. We can also call this pseudo-profundity and it’s another example of the Motte-Bailey strategy.

People like to make these kinds of statements because they are easy to defend. You can always retreat to the trivially true meaning (”I just mean we can use information theory to describe entropy!”) whenever someone points out that the “profound” meaning has no clothes.

The weak anthropic principle is another example of a popular deepity in science. In the trivial reading it just says “we observe conditions compatible with observers,” which is a tautology. In the seductive reading it pretends to explain why the universe has the constants it has, even though it adds no causal mechanism and makes no risky predictions.

Scientific Progress

As I have mentioned before, the standard model of scientific progress is not backed by facts. To use our terminology here, it’s an elegant explanation with low convergence.

But it’s instructive to map it onto our chart and compare it to a more accurate model of progress.

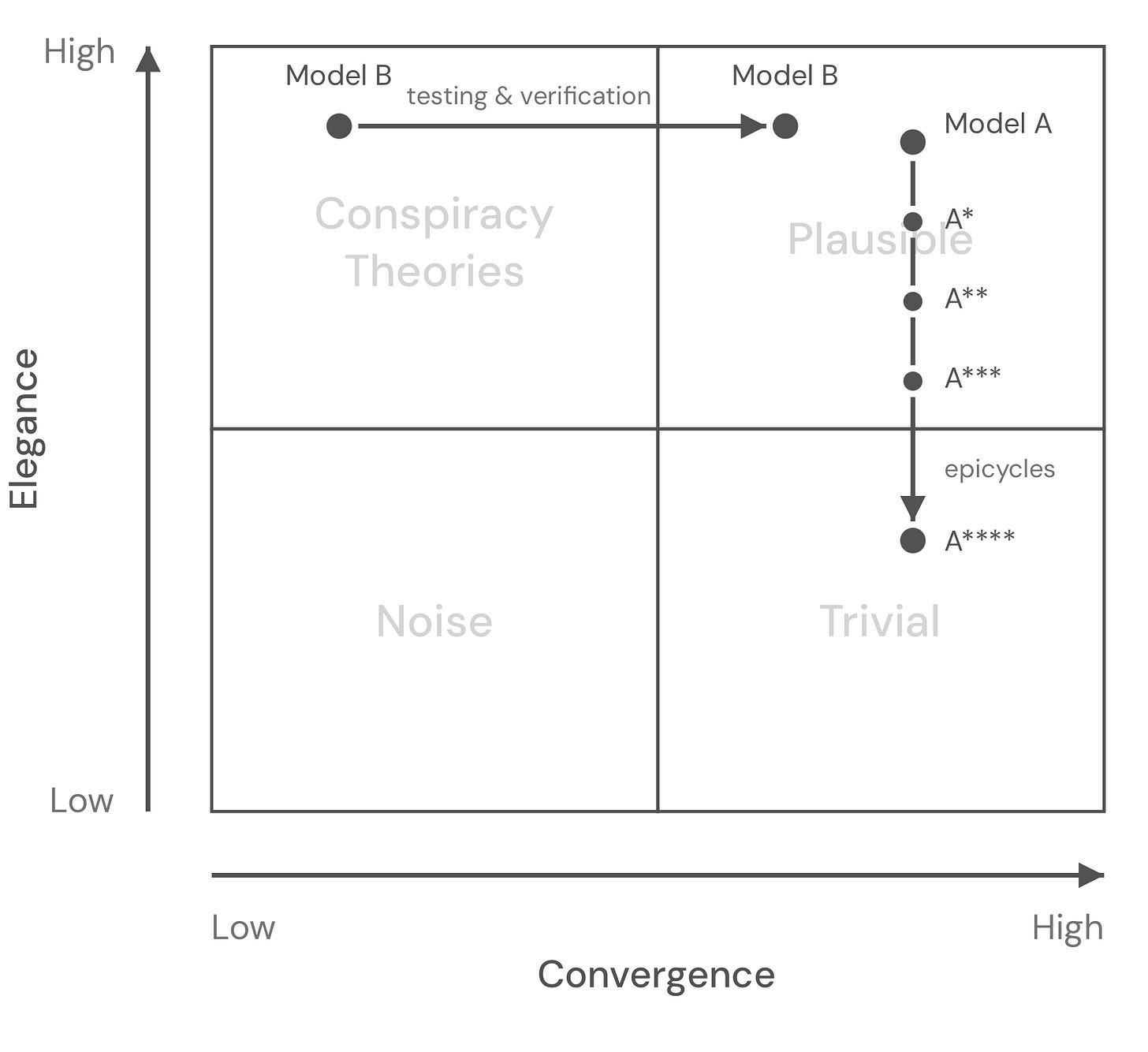

Kuhn’s model of paradigm shifts roughly goes as follows:

We start with Model A that sits in the upper right corner. It’s highly plausible since it’s sufficiently elegant and backed by mathematical consistency and experimental data.

But then new experimental data pushes it to the upper left quadrant. No longer all facts converge on the old model. This causes a “model crisis”.

This crisis is solved when a new model is proposed that is at least as elegant and has the experimental facts converge towards it.

On the other hand, a more accurate model of scientific progress is this:

We again start with the incumbent Model A sitting in the upper right corner.

New experimental evidence shows up that is not directly explained by Model A. But instead of pushing the model to the upper left quadrant, researchers quickly add small fixes. A little epicycle here, a new quantum field there. Instead of Model A we are now dealing with Model A*. In other words, researchers maintain convergence by sacrificing elegance. Researchers are usually unwilling to give up models they spent their whole careers mastering.5

Over time this makes the model less and less elegant. In our chart the model gradually gets pushed down.

Challenger Model B that eventually replaces Model A**** starts in the upper left quadrant. It’s elegant but has insufficient convergence. After all, it often takes years to work out how a given model explains a given set of experiments.

If sufficient work is put into testing Model B experimentally and putting it mathematically on solid ground, it slowly starts moving to the right. Eventually it hits a threshold where it’s plausible enough to be taken seriously.

Model Building

Once you have a proper model of scientific progress, it’s clear that most research activity isn’t very promising.

The most common approach is to take the current best Model A and then propose an incremental variation of it, Model A*. This is a safe approach since you will within a predictable time span get to a point where you can write a research paper about your work. You can easily get funding. It is easy to explain and defend since it is so close to the established model. All of these incremental model-building exercises are plausible.

The usual reasoning for this approach is entirely motivated by Kuhn’s faulty model. In short, we have to wait for a proper model crisis caused by new data that will force us to try something more radical. Until then there’s nothing reasonable to do but boring incremental research.

Except that this crisis will never come. Quantum field theory, for example, is a framework so flexible that no matter what you discover in a collider experiment you most likely can accommodate it by adding yet another field to the Standard Model of Particle Physics or add some other minor variation. And if you study the history of scientific discovery or know anything about humans it’s clear that this will always be the preferred, default approach. The scientific community has a tremendous amount of inertia.

However, ideas that elevate our understanding of nature to a truly new level virtually always start in the top-left “conspiracy” corner. They are elegant but lack convergence. New ideas are mere hatchlings that stand no chance in a fight against the full-grown eagle that is the established best model. The incumbent model had many decades to accumulate evidence of convergence. No new model can provide anything close to that right from the start. And it’s not just a lack of experimental evidence but also formal convergence. Typically few of the structural arguments that squeeze it into place have been worked out right away.

This makes it easy to dismiss new ideas. It is always trivial for experts that studied the incumbent model for years to launch devastating attacks against any idea that challenges it.

For example, when Louis de Broglie presented his framework to describe quantum mechanics at the Solvay conference in 1927, he was quickly shot down by guys like Wolfgang Pauli and Hans Kramers. Pauli’s objection was based on a misleading analogy, while Kramers demanded an explanation of a complex phenomenon that de Broglie was unable to provide on the spot. Discouraged by the criticism, de Broglie abandoned his framework. This stalled progress for more than 20 years until David Bohm rediscovered the same approach.

The elegance-convergence model provides a useful lens to understand this dynamic. As outlined at the beginning, our goal in science is of course to find plausible, or ideally profound, ideas.

However, paradigm-shifting ideas are in the technical sense, not plausible right from the start. It’s not “reasonable” to take them seriously. Hence typically no one does.

It requires someone with arational belief, following just a hunch, to propose and defend it.

On the other hand, there is a good reason why the top-left quadrant is labeled “conspiracy theories”. They also belong here. Not every elegant idea deserves to be taken seriously.6

At the same time, not everything that looks like a “conspiracy theory” (aka elegant explanations that lack convergence) should be dismissed right away.7 But unfortunately that’s exactly what happens.

No one is funding risky research on not-yet-plausible ideas in the upper-left corner. Everyone is afraid of being labeled a crackpot. This is an important factor why there is no new Einstein, why scientific progress has slowed down so much.

Just think about how crazy that is. If you spend a little time studying the history of scientific progress, it becomes obvious where most of the energy, time, and resources should be directed. If you spend some time thinking about what we are actually trying to achieve in science, the fallacies become obvious.

And yet, that upper-left corner is mostly an abandoned wasteland that no one is willing to visit.

My hope is that this framework helps a little to think more clearly about where to direct efforts. And maybe to give that weird idea in the upper-left corner a second look before shooting it down.

This terminology is from the works of John Vervaeke, Elijah Millgram, and Nicholas Rescher.

This implies Ockham’s razor. When we have two competing explanations for a given set of phenomena, the simpler one is considered more elegant. For example, supersymmetric and certain Grand Unified Models explain the same set of phenomena. However, the Grand Unified Models are significantly more economical and hence more elegant.

Instead there is good evidence that the opposite is true: “Information is not a disembodied abstract entity; it is always tied to a physical representation. It is represented by engraving on a stone tablet, a spin, a charge, a hole in a punched card, a mark on paper, or some other equivalent.”

Sports commentators love to drop deepities like “It’s just the final pass that’s not working yet”. This is trivially true when a team doesn’t score but it feels like they said something profound. Also most self-help books are deepities stretched out to hundreds of pages, dressed up with anecdotes. For example, Adam Grant’s revolutionary approach to success “Give and Take” is trivially true if you change your definition of success but unsupported if you understand success in the usual short-term, conventional, strictly materialist way.

As Max Planck observed: “A new scientific truth does not triumph by convincing its opponents and making them see the light, but rather because its opponents eventually die and a new generation grows up that is familiar with it.”

The crackpot problem is largely overblown. This is a common dynamic. You got a few students cheating and suddenly it seems like cheating is this huge problem and preventing it becomes the main objective instead of transferring knowledge. You got a few bad actors committing crimes and suddenly a whole group of society is under suspicion. You got a few crackpots making a lot of noise and suddenly every idea in the upper-left corner is dismissed. True crackpot ideas are not that hard to identify using simple heuristics. Crackpots typically have no real understanding of the problem they are trying to solve. For example, someone proposing a radical new understanding of quantum theories that is unwilling to discuss Bell inequalities is most likely a crackpot. Someone with a deep technical understanding of the problems they are trying to solve in most cases should be taken seriously. Another factor is time. Worthwhile ideas typically start accumulating evidence of convergence while crackpot theories don’t.

Also note that an idea doesn’t need to be true to be useful. Even an elegant hypothesis that turns out to be wrong can unlock new research directions, expose hidden assumptions, or reveal questions no one thought to ask. Without the wrong Aristotelian model of motion, there’s no Galileo. Without the wrong luminiferous aether, there’s no special relativity. Derek Sivers explores this in depth in his book Useful Not True. Also the line between what’s true and what isn’t often isn’t that clear cut. The Newtonian model of gravity is still tremendously useful. Or atomism, for example, once considered proven, is known to be false now in that we now know atoms aren’t actually the fundamental constituents of nature. You can even equally defend the position that there are no particles, only fields, or that there are no fields, only particles. Similarly you can flip the common interpretation of General Relativity (there is no gravity, only spacetime curvature) on its head and argue that there is no spacetime, only gravity.

This elegance-convergence framework nails why so many researchers stay in the safe zone. The deepity concept is brilliant, especially the string theory example where people shift between quadrants depending on who's asking. I've noticed how often grant committees demand both high elegance and high convergenc upfront, which basically kills any novel exploration. The de Broglie story is wild, imagine if someone had just given him space to work thru Pauli's objections instead of shutting him down.

Great essay. I think another explanatory factor in the slow down of science is the peer review system that serves to enforce a level of uniformity and "polish" to papers without increasing their quality or correctness. Scientists want their papers published and so implicitly pursue ideas that their colleagues will find more palatable, even if they are less profound.

So this is related to the fact that you point out: universities and governments are less willing to fund speculative ideas because they want to produce peer reviewed publications which go through this uniformity filter.

Historically we discovered many of our most profound scientific ideas without peer review, so it is curious we have convinced ourselves it is necessary.