Is scientific progress slowing down?

A quantitative analysis

When I was studying physics it always seemed like all the major discoveries, especially in theoretical physics, had been made many decades ago.

The Standard Model of Particle Physics reached its final form in the mid-1970s.

The Higgs mechanism, the final theoretical pieces, came in 1964.

This would hit me every year when they announced the Nobel prize in physics.

Usually it went to experimenters confirming an old model, or for theoretical work from decades ago, or for work that didn't seem that impressive.

I remember thinking several times: Really? A Nobel Prize for that?

But maybe every generation feels that way?

Maybe there was always just a huge delay between when work was done and when it is finally recognized?

I’ve decided to finally get to the bottom of this question.

Now it’s notoriously difficult to measure scientific progress in a meaningful way.

Qualitative surveys don’t work since researchers are incentivised to hype up the progress made in their field. Otherwise, funding sources might dry up.

Published papers and citation counts are flawed metrics. Publishing and citation practices have changed so dramatically over the decades that no conclusions can be drawn.

On the other hand, the yearly awarded Nobel prizes seem like a great starting point.

There has been no inflation in Nobel prizes since no more than three people in each field get the prize each year.

Hence by looking at the year when the work was done for which the prize was awarded, we might draw conclusions about the pace of scientific progress over time.

If my gut feeling was right and prizes were nowadays primarily awarded for work done many decades ago, this should show up in the data.

We also should be able to see if this was the case in previous decades.

So I wrote a quick script that extracted the data from the official Nobel Prize website.

The chart below shows the number of prizes in physics awarded based on the decade in which the work was done.

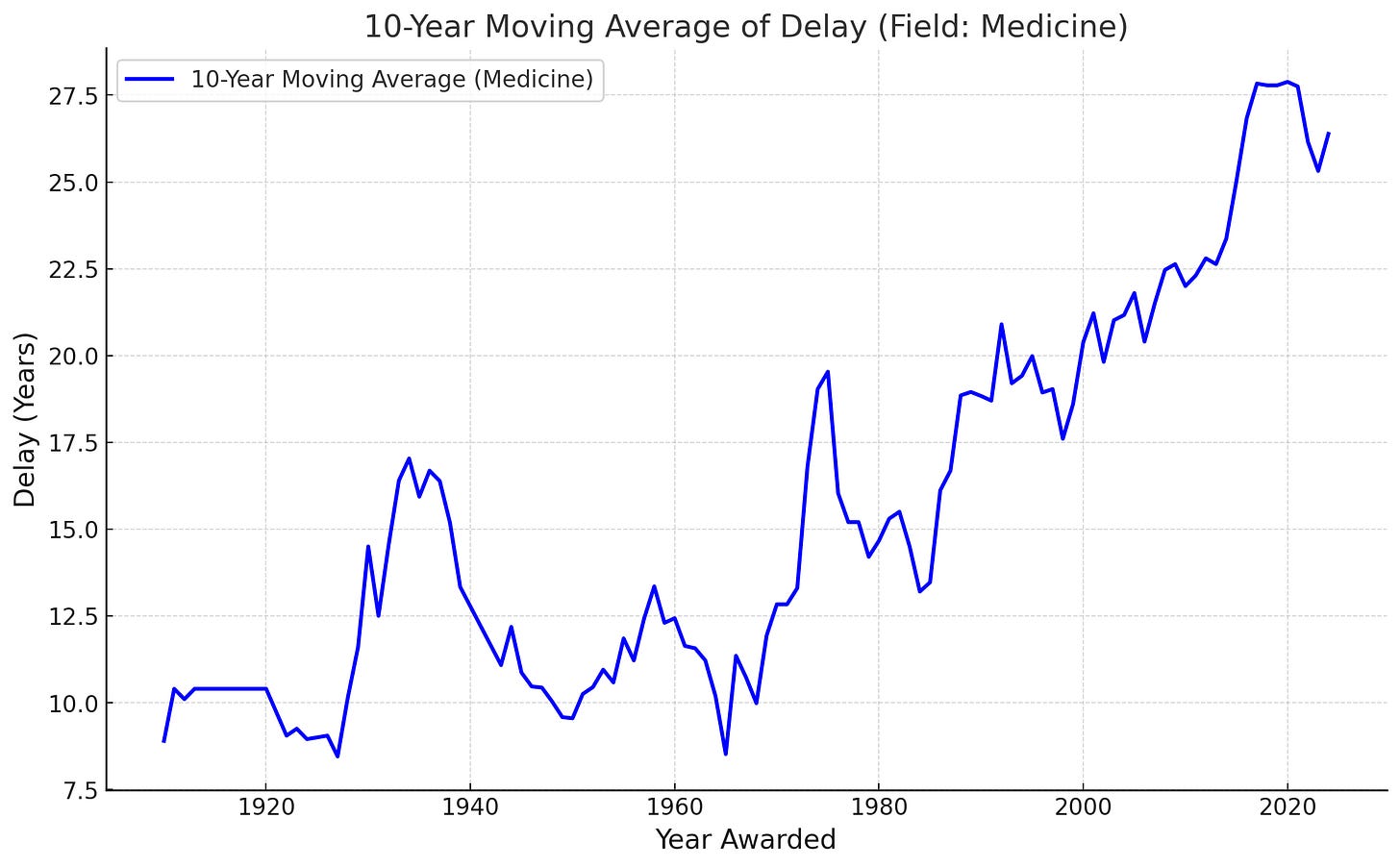

The same trend shows up in the charts for Chemistry and Medicine.

Taken at face value these charts seem to tell us that a lot more Nobel Prize-worthy work was done in the 1950s, 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s than in the decades before or after.

Another striking pattern is that little to no Nobel Prize-worthy work seems to been done in the past three decades.

There could be, however, another simple explanation. If it always takes the Nobel Prize committee 30+ years to recognize the importance of discoveries, it would be no wonder why almost no work done in the past 30 years got a prize.

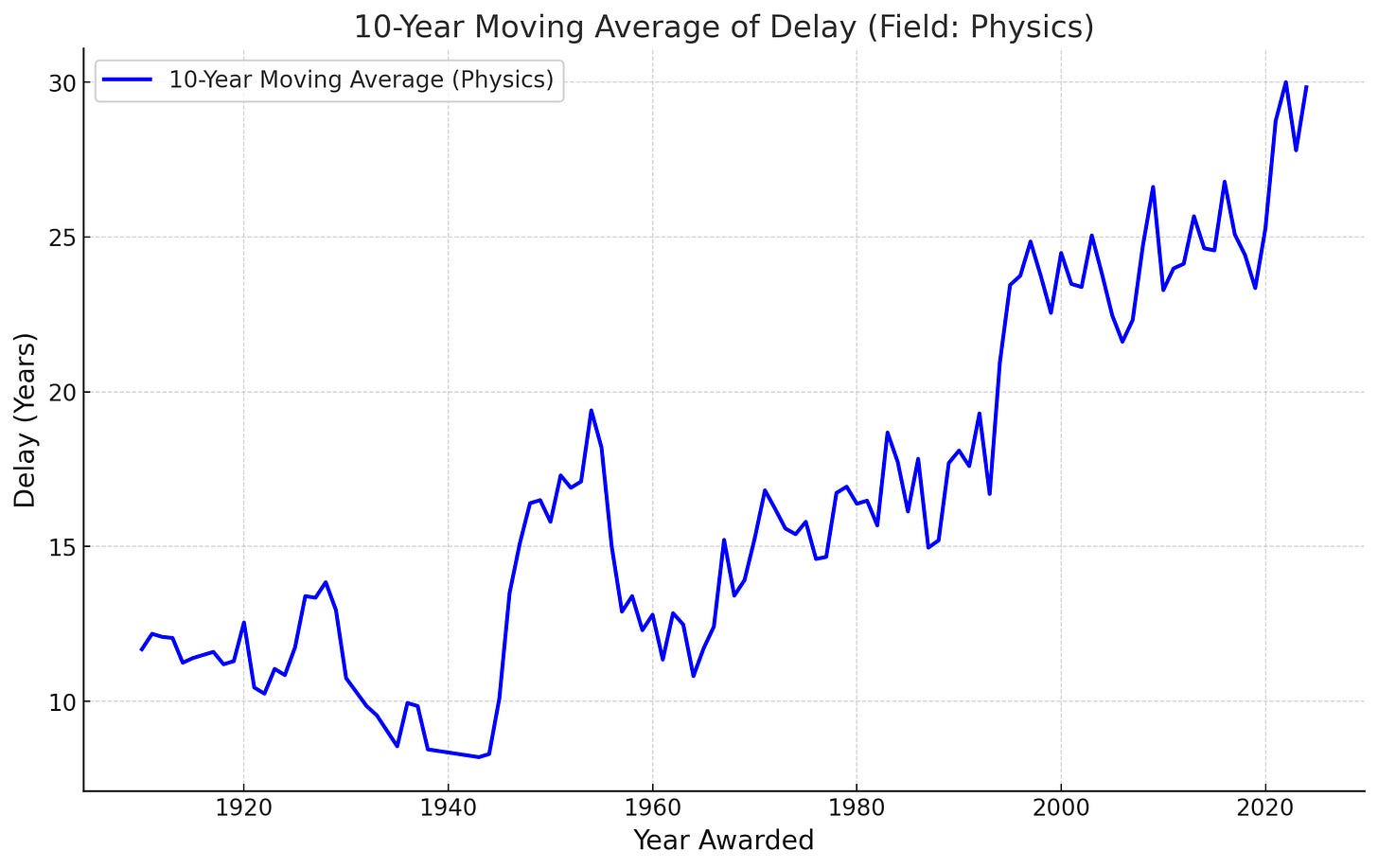

So the next thing I looked at is how the delay between when the work was done and awarded a Nobel Prize changed over time.

The chart below shows how the delay evolved over the years.

Before 1990 the average delay was 14.25 years. After 1990, the average delay is 26.04 years.

So the lack of prizes awarded for work done in, say, the 2000s is by no means normal. If the average delay was still around 15 years, we should have seen plenty of prizes awarded for work done during this period.

For example, if we imagine we had run the same analysis in 1980, this is what we would have seen:

There is, of course, a dropoff for the most recent years but a lot of the important work done in the 60s and 50s has already been recognized.

But again, there are different ways of interpreting this data.

Maybe the Nobel committee got more risk averse in recent years and this is why they started to wait longer?

Maybe the committee got dumber and fails to recognize the groundbreaking work that is done in recent years?

This could be true but I’m not aware of any plausible explanation why this would be the case.

The alternative explanation is that really fewer Nobel Prize-worthy discoveries were made in recent decades.

So the committee had to keep going back many more decades to find work that deserved the prize.

Maybe “second tier” discoveries made in the 70s and 80s are more Nobel Prize-worthy than any discoveries made in recent decades?

To figure this out we could quantify the idea that not all work that is awarded a Nobel Prize is equally important.

A few years ago, Patrick Collison and Michael Nielsen set out to do just that.

They asked scientists to competitively match discoveries against each other.

Their result? “Discoveries in physics, as judged by physicists themselves, became less important.”

In other words, the Nobel Prize committee is awarding prizes in physics for increasingly less important work.

Another sign that the Nobel Prize committee is struggling to find Nobel Prize-worthy work, is that the most recent Nobel Prize in physics was awarded for work that has nothing to do with physics at all.

The committee seems to be thinking: Instead of digging through the archives to find any work done in physics that might deserve the prize we should rather award it for truly paradigm-shifting work in an adjacent field.

Just for completeness, below is the same chart for medicine and chemistry that show the exact same trend.

So what’s the takeaway here?

It’s impossible to draw any definite conclusions from the data we looked at here. There are undeniably alternative ways to explain the observed trends.

But at least to me, the data delivers compelling evidence that scientific progress has slowed down quite dramatically in the past decades.

The reason why I’m skewing towards this explanation is that it matches my personal experience in physics.

I can’t think of a single discovery made in the past decades that the Nobel committee “overlooked”.

Many of the most interesting papers I read during my PhD were indeed written in the 1960s and 1970s.

Despite of the explosion of papers in the decades afterwards, most of them contain little of lasting value.

I also don’t hear any outcry from the research community that important recent work gets ignored by the Nobel committee.

So unlike what Betteridge’s law suggest, the most likely answer to the question in the headline “Is scientific progress slowing down?” is yes.

Now I’m aware that this is a sensitive topic.

No professors wants to hear that they contributed little in the grand scheme of things.

No one wants to admit that despite vast increases in the money spent on research little significant work is done.

If you talk about stagnation in your field you’re quickly labeled as someone who fouls their own nest since you put everyone’s funding sources at risk.

But only once we recognize the issue at hand, we can hope to solve it.

And the question why scientific progress might have slowed down is an extremely interesting and important one.

I’m highly sceptical that the correct explanation is simply that ideas are getting harder to find.

I’m not convinced that the scientific slowdown is inevitable.

But discussing this in detail is a topic for another day.

Mighty social forces, not in the least in science itself, block progress. Egotistical goals are the cause.

Thanks for pointing it out with convincing data. 💯