Scientific progress is severly understudied

Right now I’m interested in questions like Is scientific progress slowing down? and, if yes, what might be causing it?

These questions seem severely understudied.

This is puzzling because there is a widespread agreement on the importance of science.

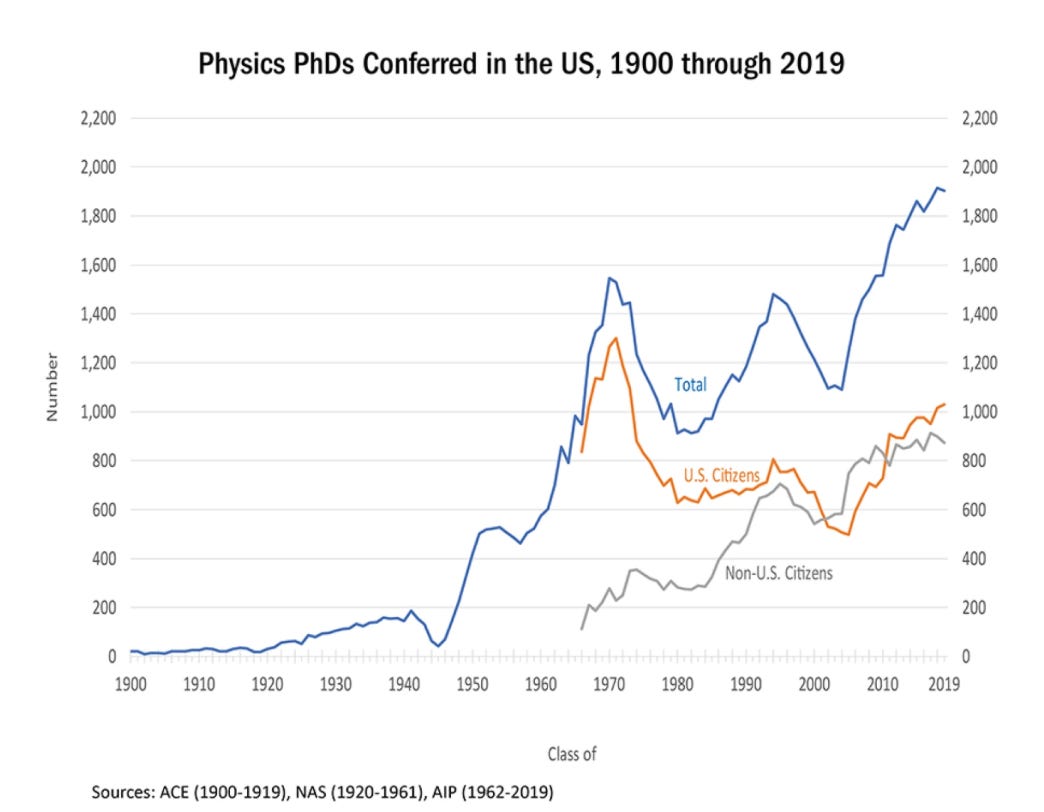

There are more scientists and more funding for science than ever before.

And yet, little seems to be known about the science of scientific progress itself.

Is all that additional money flowing into science actually leading to more progress?

Is producing more and more PhDs really good for scientific progress? At what point do we hit diminishing returns?

What kind of research problems do professors supervising 20 students assign vs. professors supervising just 2 or 3? How does the style of supervision change and what’s the impact of that?

Can we really expect that more researchers always equals more progress? Or is there a point at which you’re becoming like the guy thinking “If two guys need two weeks to get the job done, I’ll just hire 2000 guys, and the job will be done in about 20 minutes!”

How, after all, can we quantify scientific progress and measure how it evolves over time across different fields?

And once we can measure it, how can we explain the observed patterns?

For example, as I and others have argued, there is some evidence that scientific progress is slowing down and that “papers and patents are increasingly less likely to break with the past in ways that push science and technology in new directions”.

Why could that be the case?

Are we really running out of low-hanging fruit? Is it simply getting harder to make discoveries?

Or is it possibly a shift from a pursuit of truth towards measurable scientific prestige that’s causing the slowdown? When exactly did scientists become obsessed with citations? And how is that lining up against measures of progress?

How does the observed explosion in the number of authors per paper fit into the picture? Is it because more and more specialization is needed? Or is it because co-authoring is the best way to pad your publication list? And is there any evidence that “individuals search for truth, groups search for consensus”?

What role do funding agencies play? Is there a shift towards funding more established researchers or more incremental research? Can we judge funding allocation efficiency, for example, by looking at the “ratio NIH grants funded : total NIH grants submitted for Nobelists as a measure of the quality of the NIH's judgement”?

How could we enable more risky research knowing that “evaluators systematically give lower scores to research proposals that are […] highly novel”.

Is really “every attempt to manage academia making it worse”?

Does it really make sense to demand detailed multi-year plans when there is evidence that “greatness cannot be planned”? What should we make of the fact that “the paper with the greatest impact occurs randomly in a scientist's career”?

What role does the invention of measurable scientific prestige and the widespread introduction of peer review in the 1970s play?

Are researchers getting more risk-averse? If yes, why and when did the shift happen?

And what about the optimal conditions for scientific breakthroughs at a personal level?

How did the hours researchers are allocating to different activities like teaching, research, grant writing, supervising, bureaucratic tasks change over time? Is there any evidence what the optimal allocation for scientific progress might be?

What can we learn from the conditions in which breakthrough discoveries in the past were made? Should Einstein-the-patent-clerk really only be treated as a funny story? Shouldn’t it inspire institutional changes?

Moreover, it’s definitely not phenomenology but also theoretical questions that need more attention.

How many scientists still believe in some variation of the “intellectual virus” set free by Thomas Kuhn and Karl Popper? How well do their frameworks really describe scientific progress?

Do we really have to wait until our present theories are cleanly falsified before we can hope to make further progress? (In fact, “no theory, in isolation, is falsifiable.” There are usually auxiliary assumptions that can be discarded or new features can be added like epicycles to save the current theory.)

While in recent years finally some interesting work and proposals started to emerge, it doesn’t seem nearly enough. Most questions remain unanswered.

If billions of dollars are spent on science funding every year, shouldn't at least a little bit of money be spent to try to figure out how to put those funds to better use?

If the number of collectively solved problems increase in number at an average universal rate of 3.41% per decade, about equal to the rate at which average IQs increase and domestic lighing increases in efficiency (Nordhaus study), then scientific discovery should not be slowing.

Could the problem be that scientific progress is impossible to be evaluated by science itself? I think the belief that science can evaluate science itself is the prime suspect when you're looking for a cause of an impasse of some sort. You point out important issues but I think a proposition like "little seems to be known about the science of scientific progress itself" reveals the true nature of the problem. I'm not a big logician but that proposition looks like a self referencing closed loop, a tautology.

An I think that's exactly the problem: science is becoming a self referencing loop of productiveness. The numbers clearly say there's a lot of progress by scientific standards but the connection to humanity is fading and becoming unclear.

Reason is the only faculty that can evaluate science, not science itself.