No one can predict how progress is going to happen

Picbreeder is a website that allows users to “breed” evolutionary art.

You can select images you like and the system then uses a genetic algorithm to breed new art.

It works analogously to breeding horses except that instead of choosing animals to breed, you choose pictures.

What’s fascinating about the system is how unpredictable the evolution of images is. The most interesting images are the result of completely unexpected mutations.

Stepping stones rarely resemble the final product. For example, the eyes of an alien face turn into the wheels of a car.

In fact, when you’re trying to breed, say, the image of a car, you will most likely fail.

Your best chance of breeding an interesting picture is by picking the most interesting pictures at each step without trying to force a specific outcome.

Here’s how the creators of the software describe this unexpected learning: “We noticed that Picbreeder users make their best discoveries if those discoveries aren't their objective. These successful users were instead following their instinct towards the interesting and novel.”

In every instance where users ended up with an interesting final image, they had to go through a series of seemingly unrelated images.

It turns out that this is a fantastic toy model to understand how progress happens in the real world.

Breakthrough discoveries are virtually never the result of a sequence of steps anyone could have predicted.

There’s a great BBC series called Connections where historian James Burke traces how seemingly unrelated discoveries and inventions throughout history led to breakthroughs.

The mechanical loom made linen abundant, leading to cheaper paper production. This enabled book printing, which helped spread information about automated organs using pegged cylinders. French silk weavers adapted this cylinder concept, creating perforated cards to control their looms. Later, similar punch card technology enabled faster census counting, which ultimately influenced early computer design.

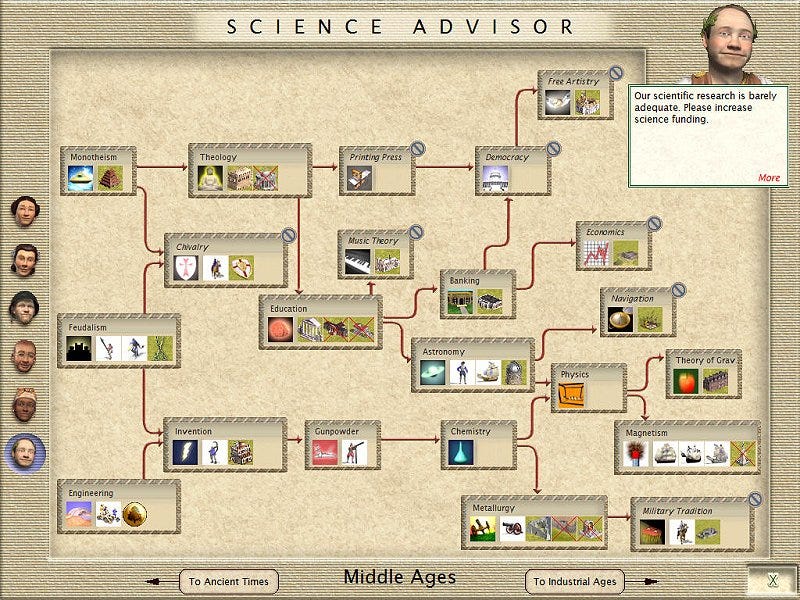

It turns out that progress in real life does not follow a clean, causal tech tree as games like Civilization suggest.

Sure, you can connect the dots in hindsight. But absolutely no one could have predicted how all of this would eventually come together.

Here’s another example.

If scientific progress followed strictly rational paths, the anomaly observed in Mercury’s movement should have led to the discovery of General Relativity.

But it didn’t. Instead, scientists stuck to the state-of-the-art theory of Newtonian gravity and “fixed” the model by adding a new planet.

And even though this hypothetical planet called Vulcan was never discovered, no one used this as a starting point to abandon Newtonian gravity and come up with a better theory.

It took a weird guy called Albert Einstein thinking about how he would feel in a falling elevator to trigger the next breakthrough.

One key to understanding why the paths of progress are so unpredictable is that a healthy dose of irrationality is often a necessary condition for breakthroughs.

Irrationality implies unpredictability.

This has important implications for anyone thinking about how to accelerate progress and innovation.

If progress is fundamentally unpredictable, it’s clear why most attempts to manage it make it worse.

Let’s return again to the Picbreeder game.

Say all experts agree that breeding the picture of a skull is the top priority right now.

Hence, the government launches a huge initiative aimed at skull image generation. They establish strict metrics and require detailed plans outlining how the goal can be achieved.

Experts develop a test to measure the skull-ness of any candidate picture on a scale from 0 to 100.

Only images that show clear progress towards skull-ness are selected. All other images are discarded.

Will this effort succeed?

Look at this sequence of images that actually generated an image of a skull.

None of the intermediate steps would have passed the skull-ness rating test.

This is why, for example, you will probably fail if you try to find a viable theory of quantum gravity by rationally combining quantum field theory and general relativity.

Physicists have been trying to do this for more than a century now with little success.

The breakthrough will most likely come from a completely unexpected direction.

If you fixate on preserving relativity’s every feature or ensuring “quantum-ness” at every step along the way, you’ll disregard the weird path that might actually lead to the correct theory of quantum gravity.

Progress requires weird tangents precisely because we don’t know where they’ll lead or why they matter.